The Victor, NY Swim Club is ranked top 20 nationally and has some of the fastest youth swimmers in the country. The club is a bit of a regional outlier given the dominance of swimming by southeast and west coast swim clubs. I asked Mike Murray, head coach, why they use Work Works as their motto. His reply, “Natural talent has limits. Those that seek to surpass the competition accept the amount of work required to be at the next level.Then, they just go to work. It is a simple formula, it is easy to understand, and effort rises to the top.”

He is onto something when it comes to young people, keeping it simple, and the value of effort.

A few weeks ago, I attended a conference focused on Education and Workforce Innovation through the eyes of policy makers, investors, and start-up founders. One of the presenters, Mr. Andy Van Kleunen, CEO of theNational Skills Coalition, continuously talked about the low supply of people who possess work-ready behaviors and attitudes— the crucial “soft skills” we hear so much about in business these days. Of course, this was notthe first time I’d heard about the desperate need for employees who demonstrate reliability, problem-solving, and capacity to work in teams.

The best way to develop workforce skills? Practice workforce skills.

At the risk of sounding like “Rick” from the Progressive Insurance commercials where he coaches young adults on not becoming their parents, I do believe there’s a simpler way to increase the volume of work-ready behaviors and attitudes: increase the volume of teenage workers.

In a recent Wall Street Journal opinion piece by Jason L. Riley, “A Little Work Never Hurt Anyone – Including Teenagers” (4/11/23), the author shares participation rate statistics of teenagers in the workforce. Unfortunately, the data shows that today only 32.8% of teens are on someone’s payroll in the workforce. Moreover, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, teen participation in the workforce has been on a steady decline since its 1978peak of 71.8%. By 1990, that number was down to 66.5%. By 2000, 61.8%. In 20 years, teen labor force participation has nearly halved to its current 32.8% rate.

Of course, employers of teenagers are increasingly competing with better and better alternatives to work: from athletics to the arts to socialization and video games. But I wonder if fewer teens participating in the labor market not only limits their own development (and economic future), but is also one of the primary causes for the ever growing challenge of finding work-ready individuals.

Many of us opine about how much we learned about ourselves and others while working in retail, hospitality, on farms, and other minimum wage jobs, in our teens. Some of the stickier lessons learned are being on time; engaging with people outside social networks; dealing with conflict; understanding the relationship between work and compensation; anticipating challenges, and experiencing both failures and successes; all of these experiences foster coping skills. Likewise, many of us experienced the relationship between performing well and earning a raise. Even if it was just an extra quarter per hour, it reinforced the relationship between being valuable to a boss and compensation.

In addition to helping to close the skills gap, there may be another upside of increasing teen employment rates: lowering underemployment of recent college graduates.

Many of us believe that the ideal worker is one that is well trained and educated, and knows how to work. One of the more underreported national statistics is the high underemployment rate of recent college graduates. In other words, the percentage of college graduates that enter the workforce in positions that do not require a college degree; it is sadly, just too high.

The New York Fed’s May 2022 data snapshot shows that 41.3% of recent college graduates were underemployed across all college majors. The rate climbs even higher when they remove graduates with college majors connected to specific licenses such as accountants, nurses, teachers, and engineers. The worst case scenario for many young people is high amounts of debt and a job market that doesn’t value their academic credential. If wewere producing well trained and education individuals, that also had a few years of work experience under their belt, underemployment would likely be lower.

With increased teen labor participation, I’m convinced workforce readiness rates would increase—and high underemployment would decrease. But this is just one piece of the puzzle as we help young people prepare for successful work life. That’s why Golisano Institute for Business & Entrepreneurship is committed to ensuring all of our graduates have the attitudes and behaviors for successful careers. With more than 50 employer partners, and soon-to-be announced entrepreneurship centers, we are immersing a diverse student body to real-world education and work. Moreover, combining a Golisano Institute credential with a bachelor’s degree via one of our traditional college partners, is a great combination.

New generations create their own priorities. They deserve the freedom to define cultural norms that make their lives joyful and satisfying. This is their moment. Still, it seems unlikely that we can produce adequate numbers of work ready people if work-preparedness begins at the age of 20+. If the current trend continues, we will face a world in which only 20% of teens work. The supply of workers, that provide value to employers, will further shrink.

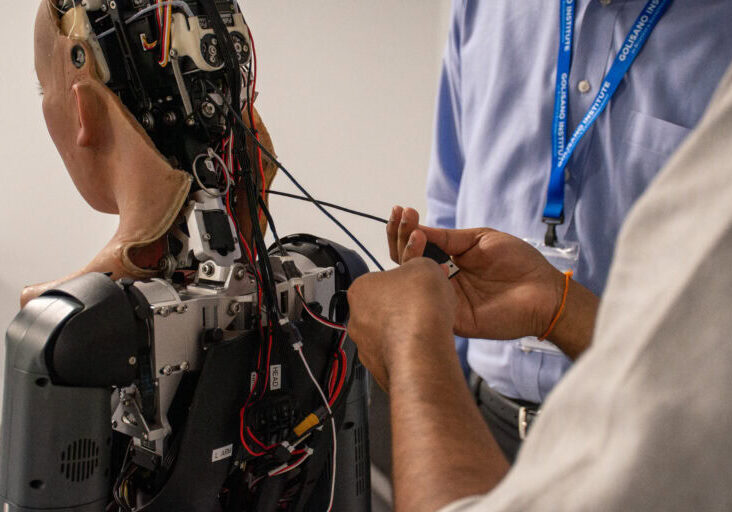

If the teen labor participation rate falls much farther, it will accelerate the need for automation to get work done. That, in turn, will further limit opportunities for economic mobility and emotional development in young people.

So, how do we boost teen employment?

Similar to college fairs, develop job fairs in high school settings. Bringing community members together with work-eligible high school students has lots of benefits.

Analyze longitudinal data on total wealth aggregation and starting age in the workforce. Do we see direct or moderating effects in the relationship between work age and long-term earnings? I am betting we will.

Link federal higher education funding to employment participation. Not only would this increase work rates, it could potentially assist higher education in developing less costly human capital solutions to operate post-secondary institutions of learning. Lastly, underemployment of recent college grads should go down.

Remove barriers to work for youth. Today, many opportunities in retail, hospitality, and other teen job markets are in the suburbs. Provide incentives and encouragement for those that may find it most difficult to see and obtain employment.

Make teen employment a state and national priority. If we agree that this is something that may help solve many economic and societal challenges, let’s focus on it.

For many youth, Work Works because it provides social-emotional development, teaches economically valuable behaviors, and maximizes other investments such as education. Our region could be a national leader by focusing on this high-reward activity.

Ian Mortimer – President, Golisano Institute for Business & Entrepreneurship

Published 7/21/23 Rochester Business Journal

Share this article

Related Articles

“The opportunity is out there. You just have to find it.”

Tom Golisano, Founder